How We Do It

"You see in this beauty a dynamic stabilizing effect essential to all life. Its aim is simple: to maintain and produce coordinated patterns of greater and greater diversity. Life improves the system’s capacity to sustain life. Life—all life—is in the service of life. The entire landscape comes alive, filled with relationships and relationships within relationships.” –Frank Herbert, Dune

Indigenous wisdom, modern application.

Our model for regeneration is the chakra integral, an indigenous agroforestry practiced in the forests of Ecuador and Peru for millennia before the arrival of Christopher Columbus. Meaning "big round garden" in the Kichwa language, the chakra integral forms a landscape that resembles a mosaic, which is economically productive and ecologically friendly to the area’s biodiversity.

Unlike conventional farms that only produce one crop like sugar or palm oil, a diverse agroforestry farm combines high-value crops like heirloom cacao and spices (turmeric, pepper, vanilla, cardamom) with nutrient-dense sustenance foods (plantain, peach palm, jackfruit and breadnut; and superfoods like acai, moringa, borojó). The diversity contributes significantly to the farmer’s income and food security, especially in remote rural communities where commercial food supplies and jobs are rare.

How agroforestry works

Agroforestry systems operate on the principle of synergy, or interactions amongst species where all actors benefit. Amidst the densely packed riot of vegetation, several distinct layers emerge: the tall trees that make the upper canopy, the shorter trees and plants that comprise the understory, the ferns and creeping plants close to the ground, the vines snaking down from the canopy, and epiphytes, or air plants, surviving on condensation.

Below ground, each type of plant plumbs the soil to a different depth. Plants on the forest floor cycle nutrients rapidly from leaf fall and other forest debris on the surface. Mature trees with deep taproots mine minerals from the depths where soil meets bedrock, funnel the nutrients up into their leaves and branches, which eventually fall to the forest floor to be recycled by other plants.

Because a variety of plants are harnessing nutrients from different levels on the surface and underground, they are not directly competing. Rather, they are helping each other.

Nature inspires our succession – and success

We implement a straightforward and proven method of succession-based agroforestry that mimics the way a forest would naturally regenerate over time.

When a forest is clearcut (or burned) and the plant life begins to regenerate, the big forest trees don't grow back first. In natural forest succession, true trees – those that live 15 years or more – will establish themselves after one or more pioneer phases.

In the pioneer phase, hardy plants (also called pioneers) grow quickly, rapidly colonizing degraded soil, accumulate biomass, open compact soil, and kickstart microbial growth. These conditions are all needed to sustain the growth of true trees.

We design agroforestry systems that respect this pattern to create an environment more hospitable to target cultivars (or cultivated plants). Target cultivars are the agroforestry analog to true trees; they are the plants that will yield food, useful materials, and income perennially – or continuously over many years.

We plant cassava and banana as pioneers intensively for one to two years. Bananas grow very quickly, reaching maturity in about a year. Their big leaves weaken and shade out the invasive pasture grass. Chopped and dropped onto the soil, the foliage also makes excellent biomass or food for the soil biome. Meanwhile, the enormous tubers of the cassava plant plumb the depths of even the tightest soils, opening up passages for beneficial insect life, bacteria, fungi, and water.

Once the soil shows signs of improvement with organic matter present, better infiltration of water, abundant insects and mycelia (the vegetative part of beneficial fungi), we follow with plantings of target crops like heirloom cacao, superfoods, and spices.

Investor Land

2018

Investor Land

2022

History as a Mirror

Indigenous ways of life and their livelihoods can teach us a lot about preserving natural resources, growing food in sustainable ways and living in harmony with nature. - FAO

Archaeological evidence here in the Chocó gives us a glimpse into the Yumbo culture which thrived here for over one thousand years—a complex, stable, and advanced culture in different ways from the societies we've been taught to think of "advanced."

The Yumbo successfully resisted Inka hegemony, not by fighting, but by maintaining "forest superiority." They utilized agroforestry systems to grow food and built complex networks of paths and raised earth mounds in the forest to conduct trade and cultivate diverse forest gardens.

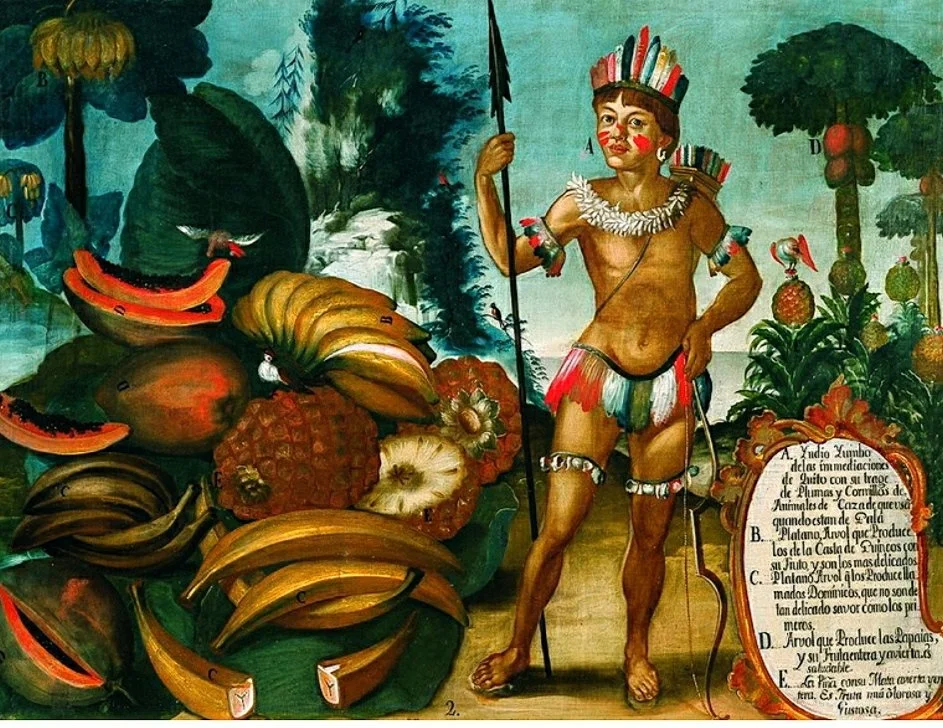

Vicente Albán, 1783. Indio Yumbo de las inmediaciones de Quito con sus trajes de plumas y colmillos de animal de caza que usan cuando están de gala. Yumbo Indian from the vicinity of Quito with their feather costumes and fangs of hunting animal that they wear when they are in gala.

Because of the diversity and abundance in their food streams, they maintained an orderly society without a large hierarchy or divisive social stratification.

The Yumbo have historical counterparts in the Marajó area of Brazil, the forest cultures of Indonesia and others. Across time and space, cultures that cultivated food via agroforestry have been more equitable, less hierarchical, healthier, and more enduring than the "great empires" we learn about in school.

You could go [along the river] where you wanted and homestead. the forest gives you all kinds of fruit and animals, the river gives you fish and plants. They had to be much more fluid, more hang loose, less coercive or people wouldn’t stay…[The people] were freer, they were healthier, they were living in a really wonderful civilization…orderly and beautiful and complex. The eye-opener was that you didn’t need a huge apparatus of state control to have all that. – Anna Roosevelt, archaeologist, author of Mound Builders of the Amazon